Healing Through Meaningful Activities

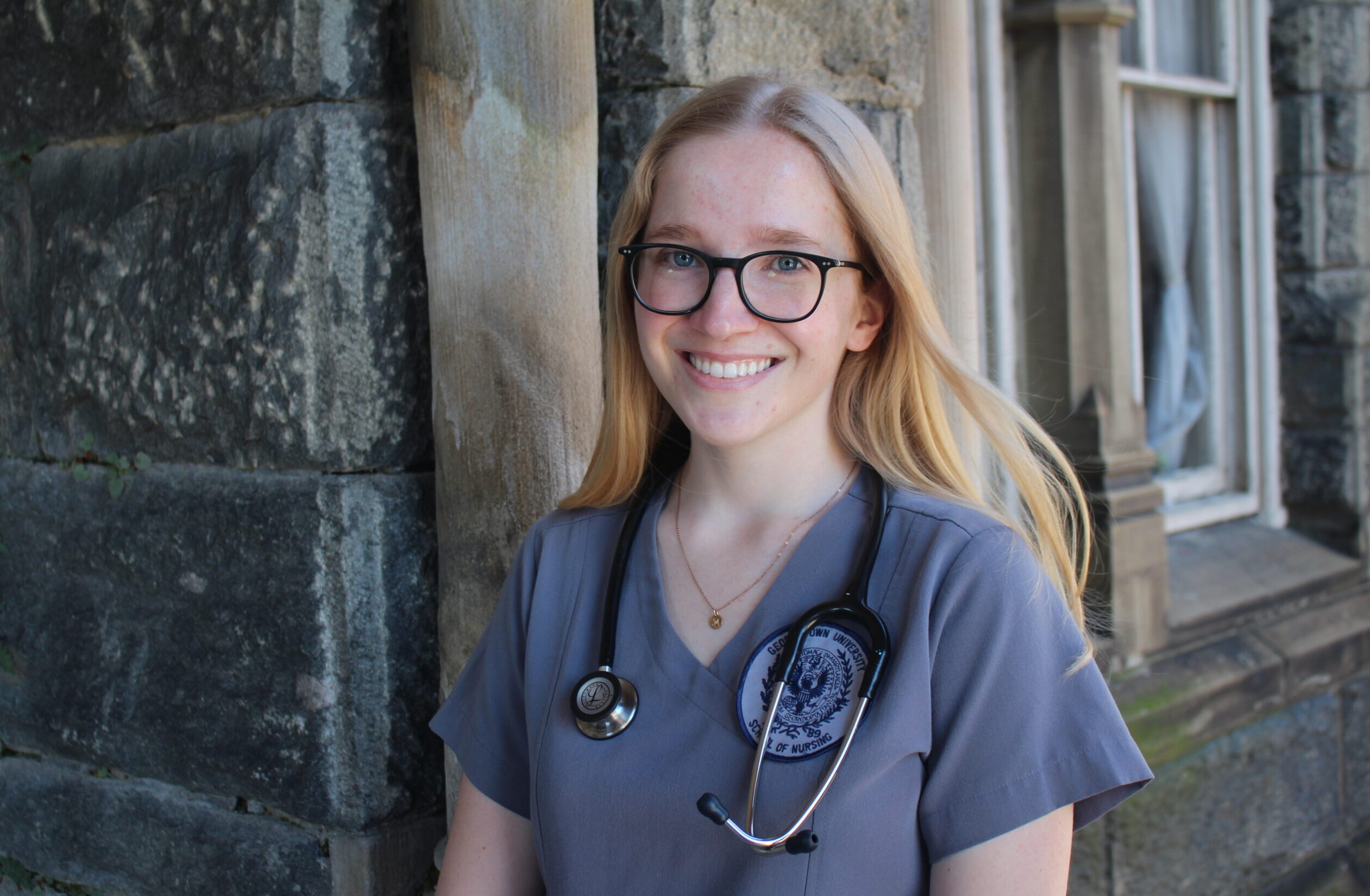

At Mountain Valley, occupational therapy informs the treatment philosophy and the environment. Our program is intentionally designed to promote healing through meaningful activities, fostering a sense of community and belonging that is crucial for recovery. Camille Wrege, MS, OTR/L, leads OT programming at Mountain Valley and came to the Upper Valley from New York, where she obtained her undergraduate and graduate degrees at Ithaca College. She’s passionate about tailoring purposeful sessions for residents that help them tap into identity and give them confidence to overcome daily challenges.

How did you decide to pursue a career in occupational therapy?

I took a trip to Costa Rica in high school and worked with kids with developmental disabilities. They struggled to access the meaningful things they wanted to do, like education or just playing with their friends. I got to work front and center with these kids before I even considered an OT program, and it was really enjoyable. I wondered if there was a job out there that could continue to help people access the things that are the most meaningful to them.

My mom introduced the OT profession to me—I had never heard of it. She had gone to school in the area and knew that Ithaca College had an occupational therapy program, so I ended up there. I’ve also always been interested in mental health, so in college I started a mindfulness club for students who struggle with anxiety. As I got more into my coursework and started learning about the body and the nervous system, I really wanted to learn more, so I focused on neuro rehabilitation.

How did you end up at Mountain Valley?

After I graduated, I started working in several different settings to gain experience. These included mainly older adults settings, a nursing home, assisted living facility, and a hospital. I loved working with people who have neurological impairments, like stroke or Parkinson’s. Although I really enjoyed that, I wanted to explore some other populations. I did a 360 and worked with the early intervention age, kids from age 0-3. That was cool too because I was still working on neuro rehabilitation and the nervous system, but it had a lot more to do with developmental delays and regulating. The job was pretty inconsistent though, and I wanted something that was more team-based and collaborative.

I love the outdoors, so I started looking for OT jobs where I could be outside, maybe with animals since I grew up on a farm. When I was searching, I also had a mental health focus in mind and Mountain Valley popped up. I’ve been here ever since.

What does a typical day look like?

I work closely with the residents in a mix of individual sessions and groups. I lead groups on Mondays and Fridays that have a lot of different themes, but they’re usually focused on engagement and meaningful occupation. We have wellness themes that focus on sleep, nutrition, and mood. We also have physical wellness groups, where we play sports like soccer and talk about the importance of movement. I really like to emphasize the importance of maintaining your health because that’s a huge part of regulating your nervous system and mental health in general.

Other groups focus on executive functioning, social skills, life skills, and connection. I do a lot of identity groups because this is a very important developmental stage for these kids, where they just aren’t sure who they are. It’s a lot of focus on who you want to be and how you want to present in the world. I usually average 10 or so residents in my groups.

Individual sessions can look a lot of different ways, but I try to keep them as functional as possible. I’m not a talk therapist and I try not to stay in the office too much—I like to go out and engage in functional activities and incorporate the skills and strategies we’re working on. For example, if I’m working on executive functioning skills with a resident, I might be coming into their room and helping them with the sequencing and problem-solving that goes into cleaning it up. I also love taking kids off campus to help them interact with strangers, people they wouldn’t normally interact with like cashiers or baristas.

It’s neat because you can take what they’re working on in therapy, like social anxiety, and combine some exposures with the hard skills from OT. I’m always collaborating with the clinicians and coming up with creative intervention ideas. But no matter what, I’m trying to relate it back to the individual based on what’s meaningful to them. Motivation is key.

Tell us about a meaningful experience you’ve had with a resident?

Recently I worked with a resident who’s on the autism spectrum and really struggles with feeling like he’s not capable and his identity in general. A lot of times in OT I like to do arts and crafts, hands-on things for motor skills work. This resident struggled with some motor skills and giving up if he’s not getting it. It’s devastating to him—it creates panic symptoms, and he shuts down. He’ll ask to leave the activity and be alone.

I noticed that one day in group and was able to see what was going on. After group I talked to him, and he was fully in a panic attack. I walked him through what we call the zones of regulation, just a simplified way of discussing the nervous system and all the states you can be in. We talked about his current state and tried to help him build more body awareness in that moment. A lot of people on the spectrum don’t have the interoceptive awareness to name what’s going on in their bodies.

After we spent some time together, he was able to go back to the activity that caused the panic attack and complete it. He was able to recognize that he could feel very intense feelings and challenge himself to be outside of his window of tolerance. It was a good session and it felt more meaningful to me because it was very in the moment and functional. We were able to work through what was impairing him in the moment, and that’s what I love about OT.

How would you sum up occupational therapy in a few words?

OT is very holistic, but the scope of the practice is so big that it can feel kind of confusing to define it. For me it’s about promoting engagement in meaningful occupations. That can look like so many different things. I’m always encouraging people to keep asking questions about how OT can be involved, the impact of it, and what it looks like in real time. I love promoting our field and the impact I get to make on a daily basis.